Chinese women switching priorities from marriage to career

SHANGHAI -- Shanghai native Huang Wei’s weekends are routine by now.

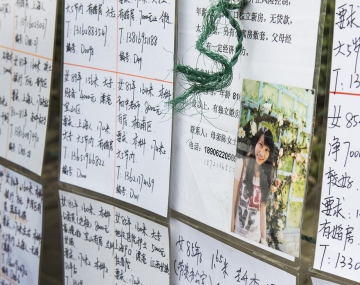

Every Saturday and Sunday morning he travels to People’s Square to scan walls of personal advertisements in the hopes of finding a woman he thinks would be a good match for him.

Every Saturday and Sunday morning he travels to People’s Square to scan walls of personal advertisements in the hopes of finding a woman he thinks would be a good match for him.

Usually he fails and walks home feeling defeated

But not today. This time, Huang, who divorced his wife 10 years ago, thinks he has finally found a woman who is a good fit for him. The 18-year-old girl whose photo stares at him from crinkled paper is 32 years his junior — and everything Huang ever wanted.

“I need a woman who will be able to give me a son or daughter and also won’t embarrass me by being better than me in terms of education or salary,” Huang explains. “I am on the lookout for women between the ages of 18-20 who don’t have the chance to make me look bad yet.”

The place where Huang believes he has met his life’s partner is the last hope for many thousands of Chinese parents who desperately want to see their daughters get married.

In a society where there is a growing number of women seeking education, many urban women are postponing marriage to have careers, which has many parents going to extreme measures, like the "marriage market" in People's Square, to pair up their sons and daughters.

In a society where there is a growing number of women seeking education, many urban women are postponing marriage to have careers, which has many parents going to extreme measures, like the "marriage market" in People's Square, to pair up their sons and daughters.

According to a census analysis by Wang Feng, director of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy in Beijing, 5 percent of urban Chinese women in their late 20s were still single in 1982. Today, that figure has risen to 27 percent.

Unmarried women in their late 20s are commonly referred to as “leftover.” Having postponed marriage, many of these women have a difficult time finding partners for strictly cultural reasons: Many Chinese men would rather be with young women who are less successful, and therefore, less likely to embarrass them personally or financially, according to Xu Anqi, the executive director of the Family Study Center at Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences.

Nevertheless, the number of women who stay single beyond the age of 25 is on the rise and is now an estimated 7 million. These women, who live mostly in urban areas, have chosen to focus on career and education rather than finding a husband, Xu said.

Following the trend

China will continue to urbanize and more women will work in higher positions and will most likely follow the model of other East Asian countries like Korea, Japan, Taiwan and Singapore, where this trend is even more common, Wang said.

“Most Chinese women will agree to marry an older man as long as he is rich and can give her a nice home to live in,” Xu said. “But the ‘leftover ladies’ don’t want that life yet.”

To the 50-year-old Huang, marrying a woman his own age is out of the question.

To the 50-year-old Huang, marrying a woman his own age is out of the question.

Though with one passing glance at the information on display, Huang can determine all he needs to know about a prospective fiancé — her name, height, father’s salary and the name of the secondary education school she attends — none of that really matters.

Huang’s chief requirement is that the woman is young. Huang says many Chinese women are willing to marry much older men if the men have high-paying jobs that will ensure a stable future.

“She will need to be able to care for me when I am older and the child we will have, so she needs to be young,” Huang said. “A woman my age couldn’t do that.”

Competing with Huang is a crowd of thousands of parents who descend on the park’s “marriage market” every Saturday and Sunday, rain or shine, scouring the area for the best options. Holding single sheets of paper that list basic characteristics about their children, parents attempt to find suitable partners for sons or daughters, many times without their child’s approval or knowledge.

One of those parents is He Yihong, a 60-year-old woman who is frantically trying to find a mate for her 34-year-old daughter. For the past four years, she has tried it all: The “marriage market,” dating websites, setting up dates with neighbors, even prayer. Unfortunately for He Yihong’s peace of mind, nothing has worked out for her daughter who rarely accepts the dates she sets up.

One of those parents is He Yihong, a 60-year-old woman who is frantically trying to find a mate for her 34-year-old daughter. For the past four years, she has tried it all: The “marriage market,” dating websites, setting up dates with neighbors, even prayer. Unfortunately for He Yihong’s peace of mind, nothing has worked out for her daughter who rarely accepts the dates she sets up.

“I just don’t really understand it,” He Yihong said. “These men I set my daughter up are handsome and have good jobs, so I don’t know why she chooses to remain single. It keeps me up at night worried about her.”

He Yihong’s daughter studied advertising at Shanghai International Studies University, and now works as a manager of a clothing company.

He Yihong’s daughter wants to continue to focus on her work, which has her mother upset. He Yihong says she believes that family is more important than work and thinks her daughter should make finding a husband to raise a family with a priority.

“I just want to be a grandmother,” He Yihong says sadly. “I am losing hope because my only child is 34 without a boyfriend or husband.”

Pei Jing, an employee at a matchmaking service, comes to People’s Square to assist in the organization of the thousands of personal advertisements displayed.

Pei said most advertisements are for women in their 20s and 30s whose parents want them to find husbands. Pei said that while there are also men advertised, women outnumber men substantially because many parents cannot accept that their daughters remain single beyond their late 20s.

Choosing career over marriage

One of those women is Susan Xu — a top editor of a Chinese newspaper — whose parents are very upset that she hasn’t walked down the aisle. But she has been too busy pursuing other dreams to care much. Like many educated, urban Chinese of her generation, she selected a Western name while studying English and continues to use it.

Shanghai-born Susan Xu, 36, attended one of China’s elite universities, Fudan University, and graduated with honors. Ever since graduation, Xu has worked her way up to the top of the newspaper business and never wanted to stop to raise a family. She admits that she has never particularly enjoyed children.

Having a successful career comes at a price for Susan Xu — many men are intimidated by her success.

“Men like a wife who is pretty but not so smart and not so hardworking, so she doesn’t embarrass him,” she said.

“Men like a wife who is pretty but not so smart and not so hardworking, so she doesn’t embarrass him,” she said.

Susan Xu said she feels the pressure to get married constantly and estimates that 99 percent of “leftover” women feel the same way. Social gatherings among neighbors are very difficult for Susan Xu who says she often feels left out because children are always the topic of conversation.

But Susan Xu said will not succumb to societal or parental pressure.

“I like being independent. I also want to be with the man I marry for the rest of my life,” Susan Xu said. “That man hasn’t come into my life, so I will continue to work to be able to support myself.”