Olive Oil: What’s In Your Bottle?

It was just another Thursday in 1986 for most Italians. But instead of being a normal sip-a-morning-cappuccino, savor-a-two-hour-lunch, Italian kind of giovedí, it was the day McDonald's arrived in Rome.

It was just another Thursday in 1986 for most Italians. But instead of being a normal sip-a-morning-cappuccino, savor-a-two-hour-lunch, Italian kind of giovedí, it was the day McDonald's arrived in Rome.

More than 300 miles away from the new set of golden arches near the Spanish Steps, Carlo Petrini saw this as the threatening dawn of fast food culture. So he began organizing the now international Slow Food movement.

Today, the Slow Food movement has 100,000 members in more than 150 countries, including America and Italy. Rather than directly opposing fast food chains and targeting globalization, Slow Food members promote the preservation of regional food traditions such as extra virgin olive oil - olio extravergine di oliva.

Deep roots in Slow Food

Olive oil is known for its deep roots and small producers, which Slow Food advocates hope to protect from industrialization - industrializzazione. Historically, olive oil has been cherished for its purity since its first use as a perfume in the Middle East during the third century B.C. Now, it is a global food made by generational family businesses and large companies alike. And, it comes in many types, including the most valuable extra virgin grade.

Olive oil is known for its deep roots and small producers, which Slow Food advocates hope to protect from industrialization - industrializzazione. Historically, olive oil has been cherished for its purity since its first use as a perfume in the Middle East during the third century B.C. Now, it is a global food made by generational family businesses and large companies alike. And, it comes in many types, including the most valuable extra virgin grade.

The United State Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the International Olive Council (IOC) both distinguish extra virgin olive oil from other, lower quality oils. The extra virgin grade is recognized chemically by its oleic acid - acido oleico - content. In order to receive its label, extra virgin olive oil must pass through tests with a free fatty acid content not exceeding 0.8 grams per 100 grams. Further, the law sets sensory requirements. True extra virgin olive oil must be free of defects and have a perceptible level of fruitiness. Even though such standards exist, olive oil regulation is voluntary and the USDA does not police the labeling of extra virgin olive oil.

As a result, olive oil labels - etichette - are evermore deceiving. Journalist Tom Mueller believes consumers depend on olive oil price tags more than labels because labels do not provide the information consumers need to make decisions. In fact, University of California, Davis researchers found that olive oil labels mislead consumers. In July 2010, they released a study proving 73% of “extra virgin” olive oils sold in California supermarkets failed to meet the internationally accepted definition for extra virgin.

“It’s one of those well-kept secrets that as soon as you get into the knowledgeable people in the olive oil community, everyone kind of knows,” Mueller said in a Skype chat. “And many of the people in the olive oil community, good and bad, know exactly where the games are being played.”

The game that Mueller refers to is particularly evident in America where rapidly increasing olive oil consumption exceeds the finite number of honest extra virgin olive oil producers. In order to satisfy consumer demands, industrial producers compromise quality for quantity. They cut extra virgin olive oil with soybean and seed oils and still label it extra virgin to make a more widely available product. Without enforced USDA and IOC regulations, it is possible to label this less valuable product as extra virgin olive oil. Then, consumers buy into it, thinking they are still getting the fresh, highest-quality olive oil while saving money.

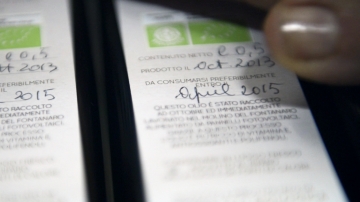

Mueller lists several ways consumers can distinguish true extra virgin olive oil from its degraded counterpart on his website, truthinoliveoil.com. The simplest way to know a bottle of extra virgin olive oil is the real stuff is to find a specific place of production - produzione - on the label. Second, a harvest date - data di raccolto - on the label indicates the freshness required in the extra virgin grade. Also, the “best by” date should be no less than two years away. Third, authentic extra virgin olive oil is packaged in tinted bottles - bottiglie - to prevent oxidation caused by exposure to light. Last, real extra virgin olive oil has bitter, peppery and fruity flavors - sapori - that confirm the presence of antioxidants found only in the extra virgin grade.

Mueller lists several ways consumers can distinguish true extra virgin olive oil from its degraded counterpart on his website, truthinoliveoil.com. The simplest way to know a bottle of extra virgin olive oil is the real stuff is to find a specific place of production - produzione - on the label. Second, a harvest date - data di raccolto - on the label indicates the freshness required in the extra virgin grade. Also, the “best by” date should be no less than two years away. Third, authentic extra virgin olive oil is packaged in tinted bottles - bottiglie - to prevent oxidation caused by exposure to light. Last, real extra virgin olive oil has bitter, peppery and fruity flavors - sapori - that confirm the presence of antioxidants found only in the extra virgin grade.

An invisible problem

Unfortunately, not all consumers understand how to tell the difference between extra virgin and other types of olive oil, let alone that there is a problem sparked by the difference. In fact, Mueller says not even one-third of olive oil consumers understand the problem in buying olive oil that is not the fresh, quality product it claims to be. This is especially worrisome for Slow Food advocates who live by quality. They are nervously witnessing a slow decline in small, local extra virgin olive oil producers as big-name brands attract more consumers with cheap products.

Not only is some extra virgin olive oil falsely labeled, it is also lacking identity - identità. Every time mass-produced olive oil passes through a factory, it loses its connection to the land on which its olives grow. French social scientist Claude Fischler addresses this problem of food identification in his article “Food, self and identity.”

Not only is some extra virgin olive oil falsely labeled, it is also lacking identity - identità. Every time mass-produced olive oil passes through a factory, it loses its connection to the land on which its olives grow. French social scientist Claude Fischler addresses this problem of food identification in his article “Food, self and identity.”

“Modern food has become in the eyes of the eater an ‘unidentified edible object,’ devoid of origin or history, with no respectable past-in short, without identity,” Fischler writes. Without identity in their food, consumers cannot establish a sense of themselves because, as Fischler explains, food determines human biological, psychological and social identity.

Truth in a bottle

Among today’s abundance of globalized, non-identifiable food, there still exist some regional products that Slow Food members promote. True extra virgin olive oil is one of those and it plays a major role in the identity of Italians.

By definition, extra virgin olive oil is a fresh product - prodotto fresco. Olives are pressed to obtain their juice the same day of harvest. There is no middleman or long trek involved in processing real extra virgin olive oil. An extra virgin olive oil producer, typically also the farmer and proprietor, ensures the oil is a product of his or her land and hands. It retains characteristics of the soil from which the olives grew and the producer’s methods bring to the oil unique traits.

At olive oil tastings, the aroma and flavor of authentic extra virgin olive oil clearly contrast with the bland “extra virgin” olive oils that stock supermarket shelves.

Even though the majority of extra virgin olive oil in American supermarkets fails to meet the definition of true extra virgin olive oil, consumers hungry for the authentic product are not out of luck. Mueller’s book Extra Virginity: The Sublime and Scandalous World of Olive Oil is just the one piece of literature that teaches consumers about globalization and the inner workings of the olive oil industry. Further, online resources, like truthinoliveoil.com, guide American consumers with lists of quality olive oil stores in nearly every state. Many of these listed stores operate websites that share product specifications and producer contact information.

Reclaiming the lost identity of extra virgin olive oil is possible with this accessibility to information about olive oil. Consumers may not have easy access to the site of production, but through online media and retail outlets they can connect with the extra virgin olive oil producer, who is oftentimes eager and willing to share their knowledge.

One of those producers is Fontanaro Organic Farm Houses in Paciano, Italy. The family-business website accommodates both English and Italian speakers. It hosts a variety of information, from product specifications to biographical and contact information. Fontanaro.it also features images of the producing family and their land that hosts extra virgin olive oil production.

One of those producers is Fontanaro Organic Farm Houses in Paciano, Italy. The family-business website accommodates both English and Italian speakers. It hosts a variety of information, from product specifications to biographical and contact information. Fontanaro.it also features images of the producing family and their land that hosts extra virgin olive oil production.

Further along in the process, Cleo’s Fine Oils and Vinegars sells Fontanaro extra virgin olive oil in Annapolis, Maryland. The store's website offers plenty of information so Slow Foodies can connect with quality Italian extra virgin olive oil, its producer and its American retailer.