Income remains barrier to equal education in South Africa

CAPE TOWN, South Africa -- Row upon row of pine green backpacks, hats and lunch boxes crowd the halls of Pinehurst Primary School. Each is stamped with the school's distinctive pine cone logo, and can be purchased in the uniform store near the lobby.

Classes at Pinehurst are held in the school's computer lab three or four times a week. Students and faculty members have their own email addresses linked to the school's website.

Pinehurst students can take art classes, music lessons and gym. The school's campus even has a swimming pool.

Pinehurst students can take art classes, music lessons and gym. The school's campus even has a swimming pool.

But about 15 miles north, in the struggling township of Dunoon, students at Sophakama Primary School may not be able to afford the required uniform, or even food to put inside a lunch pail.

The only computers at the school are in the faculty lounge, which has regularly been broken into and looted.

Sophakama students are lucky to even have a library this year. Now they don't have to travel the nearly six miles to a neighboring town to work on school projects.

This stark contrast between the rich and the poor, a legacy of apartheid, is still very visible in the schools of Cape Town. Under the apartheid system, black South Africans, as well as mixed-race or "colored" South Africans, were not taught the same curriculum as the privileged whites. In what was called the Bantu education system, blacks and coloreds were denied instruction in critical thinking skills and prepared only for low-wage, menial jobs. They spent less time on subjects such as geography and history.

Now, the generation of Bantu-educated parents and grandparents look on as their children hold the right to equal education, at least in theory. But instead of the education system being segregated by the color of skin, it is now to a great degree split by the money, or lack of it.

The cost of poverty

Experts say government funding isn't the only thing needed to solve the country's educational disparity. South Africa spent 17.4 percent of its budget on education in 2009, which is a higher proportion of state expenditure than in the United Kingdom or the United States.

But the facts remain. Many of the privileged during apartheid, though integrated now, remain privileged because of their parents' ability to pay extra fees, in addition to receiving government funding.

But the facts remain. Many of the privileged during apartheid, though integrated now, remain privileged because of their parents' ability to pay extra fees, in addition to receiving government funding.

Sixty percent of the country's students attend "no fee" or public schools like Sophakama Primary. This compares to about 90 percent of U.S. students who receive a free public school education. Many of the "no fee" schools are in black or colored communities.

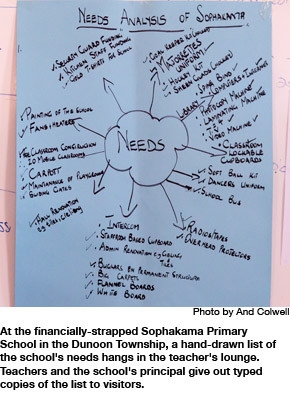

Even with 44 items on the school's "needs" list -- including fans, heaters, white boards, overhead projectors and a school bus -- Sabelo Makubalo, Sophakama's principal, recognizes that his students are better off than some other township schools.

"We are trying our best to not confine them," he said. "We are giving them life skills, reading and writing skills."

With the installation of a new library -- which was funded by an American pastor -- the school's reading scores have gone up. In May 2010, Sophakama Primary was honored for improving results on literacy tests in grade six. This is contrary to a national trend in which only 38 percent of grade six learners passed compulsory literacy testing last year. Makubalo said this may be due to a reading period the school was able to implement because of the new library.

But where math is concerned at Sophakama Primary, and throughout the country, this is a different story. Only 27 percent of grade six learners passed numeracy testing in July 2010 and only 17.4 percent of grade six learners in the Western Cape have the required numeracy skills for their grade level. South African pupils' math scores are consistently lower than countries like Zimbabwe, Botswana and Kenya -- all African countries that spend less money on education than South Africa does.

Simpiwe Gxilishe is a grade seven math teacher at Sophakama. He said he teaches math in a way that will provide students with the "everyday skills" they need or the basics of adding and subtracting.

Simpiwe Gxilishe is a grade seven math teacher at Sophakama. He said he teaches math in a way that will provide students with the "everyday skills" they need or the basics of adding and subtracting.

Though his students respond to his lessons, Gxilishe said the job is still quite challenging.

"With these kids now, I don't know where it comes from, but they're really, really struggling," he said. "They make it difficult for us."

Gxilishe said the students will usually pass grades based on age instead of proficiency level. Two out of five pupils who take South Africa's version of the Scholastic Aptitude Test will fail. Even if they make it to college, black South Africans have a high first-year drop out rate.

Gxilishe said that his students don't care that they are learning less than they could be.

"They don't know the subjects, they just do it for the sake of doing it," he said. "They know they will pass."

Yvonne Mgedezi, a grade one teacher, said the biggest problem for students at Sophakama is the environment they live in. She said the children need help from their parents at home, but many of these parents are young and uneducated, if not illiterate. Some parents also make so little money that they can't afford the small fee needed to send their children to grade R, South Africa's equivalent to kindergarten.

"Those are the ones that give a big problem," she said. "When they come [to grade one], they can't even hold a pen."

Problems at home transfer to classroom

Experts contend that South Africa's education problems and high unemployment rate go hand-in-hand. Earlier this year, unemployment stood at 24 percent nationally, as compared to the U.S. rate of about 9 percent. But the unemployment rate is much worse in the townships. Makubalo estimated the chance of the Sophakama students's parents being employed was about 50-50.

And there are other problems affecting township families, including gang wars and the AIDS epidemic.

And there are other problems affecting township families, including gang wars and the AIDS epidemic.

"If the child has a problem at home, they can't perform well," Mgedezi said.

The situation is quite different at Pinehurst Primary School, where Deputy Principal Mark Cupido said grade one students come in with "a great deal of knowledge." He added it is expected that the child would be from a "functional home" if they are from the Pinelands area.

Cupido said he doubts his students are fully aware of the differences between their school and schools in the townships -- the fact that their parents pay about 85 percent of Pinehurst's operating cost.

Many of the better schools in and around Cape Town function on this hybrid private/public spectrum. Cupido said that while the government contributes only 15 percent, the school would have trouble paying teachers a competitive salary without that funding, and more of the burden would be put on parents.

Cupido himself is a teacher educated under the Bantu system. He said when he started at Pinehurst 10 years ago he had to work to gain white parents' respect and trust.

"In the beginning parents didn't want [their kids] in my class," he said. "Two years later they were asking to have their kids in my class."

Cupido said he is surprised when Pinehurst advertises teaching positions and they get very few colored and black applicants, even though the school has become very well integrated since apartheid.

"They still think they're not worthy," he said.

All teachers must have a degree from a university or teaching college to teach in South Africa, but many teachers who became teachers before 1994 were also not initially trained the same way white teachers were. Now, testing programs such as the Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational quality have found that many teachers lack basic subject knowledge, according to government documents.

Training teachers

Xolisa Guzula, an early literacy specialist for the Project for the Study of Alternative Education in South Africa at the University of Cape Town, said her work to train Bantu-educated teachers shows that the residual effects from the old system are still a big problem.

"It's difficult to undo Bantu education because then you can only teach and produce what you know and what you have experienced," she said. "If you've learned under Bantu education you've been taught not to be a thinker. Your education was impoverished so you can produce another impoverished product. The teachers who have been through the impoverished curriculum have instilled their best, but maybe their best is not the best that is required by this system."

Though her group's primary mission is to promote "mother tongue" education that includes all of South Africa's 11 official languages, Guzula said she has worked to train teachers for as long as three years to bring them up to par on academic levels.

Though her group's primary mission is to promote "mother tongue" education that includes all of South Africa's 11 official languages, Guzula said she has worked to train teachers for as long as three years to bring them up to par on academic levels.

"We suddenly wanted teachers to produce critical thinkers," she said about the drastic post-democratic change for Bantu educators. "One week training and two workshops is not enough."

Mgedezi from Sophakama Primary is one such teacher who went for only one week of training when the system shifted. She began teaching in 1979. Despite institutional inequalities, things were not as difficult then as they are now, she said.

"That system was not OK because it was not opening our minds," she said. "This system is opening their minds, but we don't have the resources."

Lindelwa Matyeba, a grade four math teacher at Sophakama, said the school is a big step up from where she was raised in a poor region of King William's Town in the Eastern Cape. She said when it came to going through Bantu education in such an impoverished community, "You made the most of it."

"There was nothing to look forward to," she said.

The government's plan

Despite the wealth of problems with education in South Africa, there are plans to ensure teachers and students have more to look forward to. In 2010, the government announced plans to make sure that students will "attend school on time, every day, and take their schoolwork seriously," and "have access to computers, a good meal, sporting and cultural activities." In addition, the government wants teachers who, "are confident, well-trained, and continually improving their capabilities," and "are committed to giving learners the best possible education, thereby contributing to the development of the nation," according to a summary document.

Ntombizanele Mahobe, also an early literacy specialist for the Project for the Study of Alternative Education in South Africa, said South Africa's teachers and learners lack a sense of pride in doing things themselves because of all of the government's promises.

"We get promised too much," she said. "They say 'We will, we will, we will.'"

Guzala said before the end of apartheid, black and colored South Africans had more fervor for education because they knew they had to be educated to "fight the enemy." Teachers at this time were also some of the strongest activists and made their students aware of the system they faced.

"Today, we have democracy, so it feels like we are OK," Guzala said. "But we are not OK. We have a two-tiered education system, one for the rich and one for the poor."

But Matyeba from Sophakama recognizes that for today's youth, at least dreaming is now an equal opportunity.

"I do think there is a better future for them in this time," she said. "They grow as intellectual thinkers. In problem solving, they are able to read and think for themselves. Now they have the opportunity to be engineers and doctors. There is a future for them now."

About the Contributors

Andy Colwell

Graduated Dec. 2011 / Visual Journalism and Integrative Arts/Photography

Andy Colwell is a resident and native of State College/University Park/Happy Valley, at the heart of Pennsylvania. He graduated from Penn State in Dec. 2011 with degrees in visual journalism and integrative arts photography.

Andy freelances for the Associated Press and works as a wedding, portrait and event photographer in the Centre County area. His photos have appeared in dozens of publications around the world.

In addition to photographic pursuits, Andy is an Eagle Scout and played trombone in the Penn State University Marching Blue Band.

Beth Ann Downey

2011 Graduate / Print Journalism

I am one of those kids who knew exactly what they wanted to be at age 10—I wanted to be a journalist. My work in classes at Penn State, involvement in the Daily Collegian and reporting internships have made this childhood dream more than just an aspiration. I became a journalist, with a specific interest in music and culture. I graduated in May 2011 and I’m now a reporter now for the Altoona Mirror.